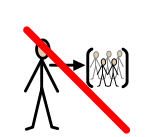

We’ve made such progress in ending discrimination in Ireland in recent years. But still, there is one group of people left out. All these years later, disability live still don’t matter.

Original article from the Irish Examiner posted 28 July 2020

by Fergus Finlay

Disability Lives Matter. I wonder how that would work as a slogan? Would anyone, I wonder, be offended, the way some people are when they hear the phrase Black Lives Matter?

You hear it again and again, don’t you, the question ‘why are you singling out black people?’ What about the fact that all lives matter? What about women, what about children, what about people of a different colour? What about, what about, what about?

All the same conditions apply — the neglect, the discrimination, the injustice, and yes — the cruelty.

There’s a great irony here. While the notion of Black Lives Matter is still contested in the US, disability lives have been changed for the better by law in that jurisdiction.

And that law, the Americans With Disabilities Act, came into being because people with disabilities refused to settle for less.

You can read a fascinating current series in The New York Times, commemorating the 30th anniversary of the Americans With Disabilities Act. Or, if you have access to Netflix, do yourselves a favour and watch a movie called Crip Camp.

It’s about a group of young people who came together, around the time of the legendary Woodstock festival, at a ‘camp for the handicapped’ as it was called then.

The name of the camp was Camp Jened. They discovered all the things that young people were discovering in those days — sex and drugs and rock and roll, basically.

But they also discovered equality. Many of the young people, who had conditions like cerebral palsy, polio, and spina bifida, had never met anyone like themselves before.

It’s a modern word, whataboutery. It’s not in my edition of the Concise Oxford Dictionary (which dates from 1990). It basically means I’m going to undermine your argument by saying you’re just a hypocrite if you don’t accept that all lives matter as much as black lives.

Of course, the real hypocrites are the whatabouters. The thing they refuse to accept is that black lives matter because they haven’t mattered in the past. The age of slavery may be gone, but racism based on skin colour is alive and well.

Black Lives Matter is important as a phrase, not because other lives don’t matter, but because black lives have been the repository of a history of cruelty, neglect, injustice, and discrimination.

It’s important as a call to arms because nothing will change unless attitudes change.

It’s important as a statement of public policy because racism has become so embedded, so institutionalised, that it’s often impervious to the established law.

So I don’t want to be accused of whataboutery — because I believe absolutely in the importance of Black Lives Matter — when I say that I think the time has come to begin to loudly proclaim that Disability Lives Matter.

The discovery that they weren’t alone, and weren’t to be pitied, was transformative.

More than 10 years after they met in that camp, many of the people involved led a major sit-in of a Federal Building, and subsequently a march on Washington, to demand the signing of a single regulation, known as 504, that would ban discrimination against people with a disability in any federally-funded activity.

Later still, and in one of the most powerful scenes from the movie, the activists got out of their wheelchairs and crawled, step by painful step, up the approach to the Capitol Building.

They wanted to symbolise its inaccessibility and to dramatise their demand for what became the Americans With Disability Act.

The Capitol Crawl went into history because it fundamentally changed the dynamic and forced people with disabilities to be listened to.

It was disability activists who led that charge. And particularly a young woman called Judy Heumann, then a survivor of polio and now a world leader of the disability movement.

Judy Heumann still says that she sometimes has difficulty understanding why she is supposed to be grateful that she can have access to a disabled toilet. It’s a sentiment that many people with a disability in Ireland — and their families — could echo.

One of the defining features of the provision of services for people with a disability here is the notion that they should be grateful for what they get.

There was a Capitol Crawl moment in Ireland. Ten years after the American Disabilities Act, the Irish government — as the Celtic Tiger was getting into full swing — decided that maybe Ireland should do something.

So they produced a Bill, the Disabilities Bill 2001 — which they announced would ‘transform Ireland’, and finally give people with disabilities in Ireland some legal rights.

It did impose some obligations on public bodies around issues like accessibility. Every obligation in the Act was qualified by language like ‘as much as practicable’ and ‘if resources permit’.

And right at the end, there was an article — section 47 — which said, in the most explicit terms possible, that the State could never be sued if it failed to carry out any of its obligations under the bill.

That piece of legislation, as phoney as it was, almost caused a revolution. A major meeting was hastily organised for the Mansion House under the slogan ‘No Rights — No Bill’, to try to prevent the bill being introduced in that form.

Despite the fact that it was an awful night — February 19, 2001 — hundreds of people turned up to protest in appalling conditions.

As one of them said from the floor — “Yes, we have disabilities. But why does that give the government the right to think we’re stupid?” That meeting could have been a turning point.

The phoney Bill was withdrawn, the minister responsible for it, Mary Wallace, effectively lost her job, and Bertie Ahern instituted a ‘consultative process’ to draw up a new Bill.

It turned out to be just as phoney as the legislation. When the movement was worn out by the consultation process (actually a very long bullying process), the old Bill was replaced by a new Bill, which contained every qualification that had been in the old one — the only thing missing was the hated Section 47.

But the result was — and still is — that the only ‘right’ people with a disability have is the right to an assessment of their needs, and to get a statement setting out what those needs are.

They have no right whatsoever to have any of those needs met.

And to this day, even when people get their assessments, usually after an endless delay, they are basically told how meaningless they are.

It’s a great lost opportunity. The great unfought civil rights campaign. We’ve made such progress in ending discrimination in Ireland in recent years.

But still, there is one group of people left out. All these years later, disability lives still don’t matter.

Audio version available

Audio version available